Paganini's Ghost Read online

Page 5

“Thank you,” Yevgeny said. “Who was that awful man?”

“Nobody,” I said. “We have to go now, I’m afraid. But I will expect you tomorrow, one o’clock.”

“I will have to check with my mother first,” Yevgeny said.

“Please do. But come alone, if you have to.”

It was a relief to step out of the reception chamber, to get away from all the people, the heat, and the noise. The landing at the top of the stairs was cool and quiet. It seemed deserted until I heard voices coming from somewhere over to my right. I turned and saw two people standing in a shadowy corner, conversing in low but intense tones. I was surprised to see that one of them was Ludmilla Ivanova. The other was a thickset man with a fleshy face and shiny bald pate that caught the light as he moved his head. They were speaking in Russian, but I could tell from their voices, and from their gestures, that they were arguing about something. Neither of them noticed us watching; they were too preoccupied with their dispute, which was becoming increasingly heated. Ludmilla raised her voice, angry now. The bald man shrugged and tried to walk away. This seemed to incense Ludmilla further, for she grabbed hold of the man’s shoulder and pulled him back, leaning close and snarling furiously into his face.

The scene made me uncomfortable. It felt as if we were spying on them, eavesdropping on a private, and very personal, conversation. I looked at Margherita and Guastafeste, sensing they felt the same. We crept softly across the landing and down the stairs. Above us, Ludmilla Ivanova was still shouting, her incomprehensible Russian words reverberating menacingly round the stone walls of the town hall.

Four

I half-expected Yevgeny to phone me the next morning to cancel our lunch appointment. He was so much in thrall to his mother that I feared she would refuse to let him come, particularly as she had not been a party to the arrangement. But in the event, they both turned up on the dot of one o’clock.

I went out to greet them on the forecourt. Ludmilla was paying the taxi driver who had brought them from Cremona, Yevgeny standing beside her with his violin case. I smiled at him warmly and shook his hand.

“Yevgeny, how nice to see you again. How are you? You have recovered from last night’s reception?”

“Yes, thank you.”

“Did you stay long?”

“Awhile. Mama enjoys these things.”

“One can’t leave too soon; it would be rude,” Ludmilla said, turning away from the taxi. “These civic receptions are an honour, Yevgeny. You have a duty to attend them.” She held out her hand. “Dottor Castiglione, it is kind of you to invite us.”

“Please call me Gianni.”

“Then you must call me Ludmilla,” she said graciously.

If she harboured any resentment towards me for insisting that she leave my workshop the previous afternoon, it certainly wasn’t obvious. She seemed in a good humour, her face relaxed and benign. She was wearing another low-cut dress—a tight royal blue one that clung to her full figure—and matching shoes. Her long black hair hung loose over her shoulders, and round her neck was a silver chain from which a sapphire cluster dangled.

“We are playing quartets?” Yevgeny asked.

“If you still wish to,” I replied.

“Of course. That is why I bring my violin. Are the others here?”

“Antonio is. Our viola player, Father Arrighi, will be here shortly.”

“Father? He is a priest?”

“When you play quartets the way we do,” I said, “it helps to have God on your side.”

We went into the house. I settled Yevgeny and Ludmilla in the sitting room, then walked through into the kitchen, where Margherita was preparing a tray of antipasti, Guastafeste loitering awkwardly in the vicinity, trying to appear willing but not actually doing anything useful. I asked him to make some aperitifs for everyone and he accepted with alacrity, rummaging in my cupboards and bringing forth all manner of spirit bottles, some of which I’d forgotten I had. Antonio’s drink-mixing skills are legendary. His aperitifs, a potent concoction of gin and vodka and anything else he can lay hands on, are guaranteed to whet your appetite—if they don’t knock you out first.

He was arranging the drinks on a tray when—with the impeccable timing for which he was renowned—Father Ignazio Arrighi arrived.

“He knows,” Guastafeste whispered to me as the priest came into the kitchen. “Somehow he always knows. He must be able to smell booze on the wind or something.”

“Ah, just what I need,” Father Arrighi said, helping himself to one of the glasses.

He was wearing his dark suit and dog collar, his soft pink face glowing with good health. I knew he’d had a busy morning—Mass at seven-thirty for the early risers, then another at ten for the laggards—but he was free now until the evening. The Catholic Church is a civilised institution. It realised long ago that the well-being of a congregation, and its priests, is dependent on a long lunch and a nap on a Sunday afternoon.

I took him through into the sitting room and introduced him to the Ivanovs. Guastafeste followed with the aperitifs. I helped distribute the drinks, then excused myself and returned to the kitchen. Margherita was at the sink, busying herself with some washing up.

“Leave that,” I said.

“I’m just clearing a few things out of the way,” she replied.

“Go and sit down with a drink.”

“I will. But I’ll just—”

“Now,” I said firmly. “I didn’t invite you here to do the washing up.”

“You can’t do it all yourself, Gianni.”

“No arguments,” I said. “Out.”

“What about the pasta sauce?”

“Out!”

I shooed her out of the kitchen. She went, but only reluctantly. We are both of a generation that grew up with entrenched views about the respective roles of men and women. My wife, when she was alive, did all the cooking and virtually all the other household chores. It was how things were. The world has changed since then, though perhaps not as much as we would like to think. Margherita is an independent, liberated woman who, by her own admission, loathes the drudgery of domesticity, but the traces of convention are hard to throw off. There was something in her that would not allow her to put her feet up and do nothing when there was work to be done in the kitchen.

I checked the tomato sauce that was simmering on the hob, then the pork escalopes in the oven. I am a latecomer to the art of cooking and my repertoire is relatively limited. I have learnt a few new dishes in the seven years that I’ve been a widower, but my staple diet is still essentially the same food that Caterina cooked for us during the thirty-five years we were married—pasta, chicken and pork, plenty of fresh vegetables. It is a simple, unfussy regimen, but then, I am a simple, unfussy person. The food suits me well enough, and I am not embarrassed to serve it to my guests. I am a sixty-four-year-old man who lives alone. People do not expect me to provide cordon bleu meals. They are generally amazed that I can even boil an egg.

We ate in my small, rather cramped dining room. In summer, I like to eat al fresco on the terrace, but it was now October and too chilly to sit outside. It was a pleasant, sociable meal. Guastafeste, Father Arrighi, and I have known one another for many years. Margherita has been a feature of my life for only twelve months, but already she is comfortable with my friends, and they with her. The Ivanovs were easy guests. Yevgeny said very little, but Ludmilla more than made up for his reticence.

“Tell me,” I said to her at the end of the meal. “How did you learn to speak such excellent Italian?”

We had finished the cake that Margherita had brought with her from Milan and I was passing round some torrone, the honey and almond nougat that is a Cremonese speciality. Guastafeste was topping up our glasses from a fresh bottle of wine and carefully leaving the half-full bottle next to Father Arrighi.

“I studied here,” Ludmilla said. “When I was younger. I was a student at the conservatoire in Moscow, but I came to Milan for a ye

ar, to the conservatorio.”

“You play an instrument?” Guastafeste asked.

“I was a singer.”

So I had guessed correctly the day before.

“You sang professionally?” I said.

“For a short time. Then I met my husband and had Yevgeny and”—she smiled tenderly at her son—“suddenly my career was not so important.”

“Your husband is travelling with you?” Father Arrighi asked.

“My ex-husband,” Ludmilla said carefully, “is living in Moscow with his second wife.”

“Ah, I’m sorry I asked.”

“Not at all. Fyodor and I were divorced a long time ago, when Yevgeny was only a child. It is all in the past.”

I made coffee for everyone; then we went through into the back room to play quartets.

“Let me apologise now for our poor standard,” I said to Yevgeny as we took out our instruments. “If at any time it all becomes too excruciatingly awful for you, you must say so and we will stop. We do not want to torture you.”

“We do this for fun,” Yevgeny said. “I do not care how you play.”

He was holding his Stradivari in his hand.

“May I?” I said.

He passed the violin to me and I ran my eyes over it. I could tell at once—from the warm dark colour, the long corners, the handsome two-piece maple back—that it dated from the early 1700s, the beginning of Stradivari’s “Golden Period.” He was in his late fifties then, not much younger than I was. Like me, he’d been making violins for more than forty years, although there the comparison ends. This was an exquisite violin, far surpassing anything I have been able to create in my own, not entirely undistinguished, career. I have examined many Stradivari violins and I have never once felt jealous of his unique skill as a luthier. He is such a world apart from everyone else that it would be like a mortal envying a god. I am just glad that he lived, and that his work has survived for new generations of violin makers to enjoy and attempt to emulate.

I couldn’t help comparing this instrument with Paganini’s, the Cannon was so fresh in my mind. Guarneri del Gesù—literally, “of Jesus,” because of the cross he inscribed on his labels—and Stradivari were very different characters as men, and those differences are readily apparent in their violins. Stradivari was a perfectionist, an austere, serious sort of man who led a life of hard work and sober propriety. Guarneri was a wilder, less focused character—much like the rest of us—who got drunk on a Saturday night and didn’t give a damn if some of his work was slipshod. Stradivari’s instruments are meticulously crafted, every detail given care and attention. Guarneri’s—particularly il Cannone—are rougher, louder, but don’t be fooled by appearances. The trappings may be different, but underneath they both sing like angels.

I peered inside the f-hole, tilting the violin towards the light so I could read the maker’s label: Antonius Stradivarius Cremonensis Faciebat Anno 1701.

“It is not mine,” Yevgeny said. “I could not afford a violin like that. It is on loan from the Moscow Conservatoire.”

“It’s a fine instrument,” I said, handing it back reluctantly, then picking up my own violin—one I made myself, of course—dating from what I like to think of as my own “Golden Period,” which lasted for about a fortnight in 1985.

“What shall we play?” Guastafeste asked. He was already seated in front of his music stand, his cello between his legs.

“Let Yevgeny decide,” I said. “What would you like?”

“I do not know,” Yevgeny said. “There is so much to choose from. Help me, Gianni. Where do I begin?”

“At the beginning,” I said.

So we played Haydn, the father of the string quartet, then moved on to his heirs, Mozart and Beethoven, sometimes just playing single movements rather than whole works. Yevgeny was happy to dip in and out, sampling a range of composers. He was like a child opening birthday presents, delighted to find something else to unwrap and enjoy.

I was relieved that he didn’t want to work on the pieces, to practise the tricky passages. Over my years as an amateur quartet player, I have come to realise that practising the difficult bits doesn’t really make you play them any better; it just hammers home the depressing conclusion that you’ll never be able to play them.

The string quartet is, in theory, a unified musical form comprised of four equal parts, each as important as the next. In practice, the first violin is more equal than the others, which suited Guastafeste, Father Arrighi, and me perfectly. We could sit back and allow Yevgeny to dominate. We could listen and relish his wonderful sound. Never before had we played with a violinist of his stature. He was accustomed to being a soloist, to being the star, but he was too good a musician to swamp the ensemble with his superior technique. He did his best to blend in, to avoid humiliating us, though the vast gap between us was patently obvious to everyone in the room.

Margherita and Ludmilla sat in the armchairs against the back wall, listening raptly. When we played the cavatina from one of Beethoven’s late quartets—one of the most beautiful pieces of chamber music ever written—I glanced at Margherita and saw she had tears in her eyes. Antonio and Father Arrighi were also showing signs of emotion, not just at the music but at the memories it brought back. The cavatina was one of Tomaso Rainaldi’s favourite pieces, and this was the first time we had played it together since his death. This was the first time, in fact, that we had played quartets at all.

Losing our first violinist had been a traumatic experience. Having Yevgeny filling the gap was musically rewarding, but Tomaso had been a friend since childhood; we had made music together for fifty years. No one could take his place, either in my life or in our quartet. I found my own eyes watering as I remembered him, remembered all those happy moments we’d had together, and at the end of the movement I made my excuses and hurried from the room.

Margherita found me in the kitchen a few minutes later, dabbing at my eyes with a handkerchief. She didn’t say anything, just put her arms round me and drew me close, holding me until I’d composed myself.

“It was Tomaso, wasn’t it?” she said, pulling back from me.

I nodded. Margherita had never met Tomaso, but I’d told her stories about him.

“That piece in particular,” I said. “Tomaso loved it so much. We used to joke about it. ‘Not the cavatina again,’ we used to say when Tomaso suggested it.”

“It’s a very moving piece of music. And you played it so well.”

“I know. Yevgeny is terrific, isn’t he? I’m sure he played it better than Tomaso ever did, but the funny thing is, it didn’t feel as if he did. Do you know what I mean? It didn’t feel right, didn’t sound right, because it wasn’t Tomaso playing it.” I wiped my eyes again with my handkerchief. “All the time, I was thinking, I am never going to hear Tomaso play this again. I am never going to see him, speak to him, make music with him. He’s gone.”

Margherita hugged me again.

“I know,” she said gently. “It’s hard, isn’t it? Memories are painful, but they’re also uplifting. He’s still with you, Gianni. You have to look at it like that. Tomaso has gone, but a part of him is still here with you, and always will be.”

She smiled at me.

“Why don’t you take a break now? You’ve played enough. I’ll make tea for us all.”

I took her hand and held it tight.

“Thank you. I’m glad you’re here.”

“You can always talk to me, Gianni. You know that.”

I went out into the garden for a time to let the fresh air clear my head. It had been many months since I’d shed tears for Tomaso, but grief is like that. It’s not a continuous process; it comes in waves. You can keep it at bay for a time, like a dam holding back a lake, but then something triggers an explosion inside you, shattering the wall and letting loose a flood. With me, that trigger is so often music. Music, more than anything, has memories, associations, and it works on a subliminal level that is somehow more powerful

than more overt influences. Photographs, remembered conversations, geographic locations—they can all release that torrent of emotion. But music seems to probe deeper, to find the most raw, sensitive part of me, and the resulting deluge is all the more overwhelming.

The afternoon sunshine, the breeze gusting across the plain soothed me, dried my damp cheeks. I picked a few late French beans and a courgette from my vegetable patch, then heard footsteps behind me. I turned and saw Yevgeny approaching.

“You are all right?” he asked, his face concerned.

“I’m fine.”

“I have not tired you too much?”

“Not at all.”

“I know we play a lot. But it has been such fun. All this wonderful music I never play before. Thank you.”

“Thank you for joining us,” I said. “To play with a violinist like you has been a great privilege. I’m sorry we can’t match you.”

“You play well, all of you. And I see you love playing. That is good. In my world, the professional world, it is not always fun.”

He looked round the garden, at the shrubs and trees, the surrounding fields rolling away into the distance.

“It is very peaceful,” he said. “You always live here?”

I shook my head.

“I lived in the city for many years. I like the countryside, but it was better for my children to be in Cremona. That was where their schools were, their friends.”

“You have children?”

“Two sons and a daughter. All grown up and settled elsewhere now. I have three grandchildren, too.”

“In Cremona?”

“Mantua. Not far away.”

“It must be nice to have family,” Yevgeny said. “Friends, too,” he added with a pensive frown.

“You have friends, surely?” I said.

“Not really,” he replied. “My life, from age four, has been violin and nothing else—lessons, practice, concerts. Those things boys do—playing football, going to parties, cinema—I do none of them.”

I felt sorry for him, but I wasn’t surprised by his revelation. I have encountered a large number of gifted musicians in my time as a luthier, and none of them has had what I would regard as a proper childhood. Childhood and musical excellence are not compatible with each other—you have to make a choice between the two. I could sense the loneliness in Yevgeny. I could imagine the isolated kind of life he’d led—the years of single-minded practice he’d had to put in to reach his current position. And he was one of the lucky ones. He’d survived, come through it all to establish himself as a soloist, but I knew there were thousands more just like him who had fallen by the wayside. They had sacrificed their youth to music and then found there was no place for them in the adult world.

Attack at Dead Man's Bay

Attack at Dead Man's Bay Paganini's Ghost

Paganini's Ghost Escape from Shadow Island

Escape from Shadow Island The Rainaldi Quartet

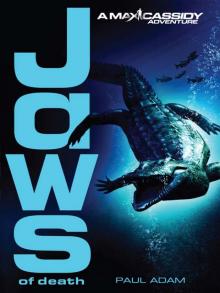

The Rainaldi Quartet Jaws of Death

Jaws of Death