Escape from Shadow Island Read online

Page 8

“Who knows? That depends on the judge.”

“We’ve been waiting two years already. How much longer is it going to be?”

“That is impossible to say. Two, three years, maybe longer.”

“Three years?” Max exclaimed. “My mum has to stay in jail for another three years before her appeal is even heard?”

“Three years is not long time.”

“It is to my mum,” Max exploded. “And it is to me. Three years!”

“Can nothing be done to speed it up?” Consuela asked.

Estevez sucked hard on his cigar, then puffed smoke into the air. “Is possible,” he said.

“What do you mean?” Consuela said.

“I mean, is possible if we make arrangement with judge.”

“You mean bribe him?” snapped Max.

“No, no, is not a bribe. It is arrangement fee. There is difference.”

“And how much would this fee be?” Max said.

“I don’t know. Ten thousand dollars. Twenty.”

“Twenty thousand dollars? Are you serious?”

“Is serious business,” Estevez replied. “Your mother is convicted of murder. To get off murder conviction cost big money.”

“But she’s innocent,” Max said.

Estevez looked puzzled by this remark. “What difference that make?” he said. “She in jail. She want to get out, she have to pay.”

“What kind of stupid legal system have you got here?”

“That how things work in Santo Domingo. You pay judge, you get appeal hearing. You no pay, you wait.”

“And all the money we’ve been paying you?” Max said. “What’s happened to that?”

“That for my expenses. For work I do,” Estevez said.

“What work?”

“Eh?”

Max pushed back his chair and stood up. He turned to Consuela. “Let’s go, we’re getting nowhere here.” He headed for the door.

“Hey,” Estevez called after him. “What you do? You want me to make arrangement, or not?”

Max ignored him. He walked out through the secretary’s office and into the street.

Consuela hurried after him. “Max, wait!”

Max kept going. Only when they were well away from the lawyer’s office did he stop. He leaned back on the wall of a building and let out a deep breath, trying to calm himself down.

“Sometimes you’re so impetuous,” Consuela said. “Estevez is your mother’s lawyer.”

“He’s a liar and a crook,” said Max.

“We need him.”

“For what? He’s taken our money for two years and done nothing at all for it. It’s over.”

“You’re firing him?”

“You bet I am.”

“Max, don’t be rash. Without a lawyer, how are you going to help your mother?”

“Having a lawyer hasn’t helped her so far, has it? He’s just milking us dry. You saw him. He’s nothing but an idle drunk.”

“But he knows the system here. We don’t.”

“If I thought it would make a difference, I’d find twenty thousand dollars to bribe the judge. I’d find fifty, a hundred thousand, if I could be sure it would get Mum out of prison. But it won’t. Estevez will take the money for himself, or the judge will take it but then demand more to let her off.”

“What alternative do we have?” Consuela said.

“Mum’s in England, not Santo Domingo. We cut the Santo Domingo courts out of it,” Max said. “We find evidence to show conclusively that she didn’t kill my dad and we take it to an English court. They’ll have to listen to us, and if they don’t, we’ll go to the press, the media, and make a fuss until they do.”

“And where are we going to find this evidence?”

“I don’t know,” Max said. “But I know where we have to begin looking.”

8

THE TWO ARMED GUARDS AT THE ENTRANCE to the Playa d’Oro holiday resort were big men in khaki uniforms and heavy combat boots. They were private security officers, but they looked like soldiers. They wore wraparound sunglasses and peaked caps over short army-style haircuts, and cradled in their arms were gleaming semiautomatic rifles.

The taxi that brought Max and Consuela out from Rio Verde stopped at the checkpoint. One of the guards leaned down to ask for their passports. As he did so, his eyes flicked around the interior of the taxi before scrutinizing the occupants. Max got just a cursory glance, but Consuela was subjected to a long, lingering inspection.

“British?” the guard said, studying Max’s passport.

“Yes.”

“And Spanish?”

“Yes,” Consuela replied.

“You are staying here?” the guard asked.

“Just visiting for the day.”

The guard took their passports over to the hut beside the checkpoint and entered their details on a computer. While he was doing this, his colleague checked the trunk of the taxi and ran a mirror on a stick along the ground to check the underside of the car. Some of the richest people in the world stayed at Playa d’Oro. And rich people expected the highest security.

The first guard came back out of the hut. He returned the passports to Consuela and handed her two day passes.

“You must give these back on your way out,” he instructed them.

The steel barrier blocking the road rose silently into the air, allowing the taxi through. The contrast with the world outside the resort was immediately apparent. The road from Rio Verde had been rough and full of potholes, the land beside it brown and dusty. In the shantytown in the suburbs, skinny, malnourished children had played barefoot beside open sewers. But here in Playa d’Oro the road was smooth and spotlessly clean as if it were scrubbed with disinfectant every night. There were beautiful landscaped gardens on one side—rolling lawns and flower beds packed with luxuriant tropical flowers; on the other side was a golf course with velvety fairways and greens broken up by small shimmering lakes and bunkers of pure white sand.

Ahead of them, half a mile in the distance, was the resort complex—a huge fifteen-story hotel, a domed casino, restaurants and shops—and the theater where Max’s father had performed for the last time. The buildings were spread out over a broad plain just behind the golden beach—it looked more like a small town than a holiday resort.

“Wow!” he said. “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

“It’s quite something, isn’t it?” Consuela agreed. “It’s so big there’s a shuttle bus to take guests from one end to the other. Some people live here all year round. They never have to leave. Everything they could possibly want is provided.”

The taxi stopped outside the main entrance to the hotel. A porter in a crisp green-and-gold uniform stepped forward and whipped open the rear door of the taxi for Max and Consuela to climb out.

“Good morning, madam, sir. Welcome to Playa d’Oro,” he said in English. He was Santo Domingan, but English was the main language of Playa d’Oro, as most of the guests were American or European. “Do you have any luggage?”

“No, we’re just visiting,” Consuela replied.

“The visitors’ information desk is just inside the hotel lobby. Enjoy your time at Playa d’Oro.”

Consuela paid the taxi driver and they watched him drive back toward the exit.

“Where do you want to go first?” asked Consuela.

“Show me where Mum and Dad stayed,” Max said.

The bungalows were near the beach. To get there they had to walk past one of the resort’s many cafés and swimming pools. The pool was almost the size of a soccer field, the terrace covered with lounge chairs on which bronzed guests in swimsuits were sunbathing. Waiters in white uniforms moved back and forth from the café, delivering drinks and snacks.

“It’s a nice life, if you can afford it,” Consuela said dryly.

“It looks boring to me,” Max replied. “Just lying around frying in the sun.”

The path dropped away from the terrace through

a shady grove of palm trees and shrubs before emerging beside a cluster of straw-roofed wooden bungalows, each with its own veranda and patch of garden. Consuela showed Max the one where his parents had stayed.

“They each have a double bedroom, a bathroom, a sitting room, and a small kitchenette.”

“Where did you stay?” Max asked.

“I was up in the main hotel building. Your father was a celebrity. That’s why they gave him one of these beach places.”

Max studied the bungalows. There must have been forty or fifty of them, but they were well spread out among palm trees and lawns so each one had some privacy.

“And the rocks where my dad’s stuff was found…?” he asked.

“Down here.”

Max followed Consuela farther along the path to the top of the beach and a cluster of jagged black rocks.

“His jacket was dumped about there,” she said, pointing. “His wallet was just beside it. His money and credit cards were still inside. That’s why the police ruled out robbery as a motive for his murder.”

“If he was murdered,” Max said. “And the knife?”

“It was down there, in that crack between the rocks. I didn’t get a close look—the police cordoned the area off immediately.”

Max crouched down and peered into the crack. There seemed something peculiar, creepy even, about what he was doing: examining the scene where his mother was alleged to have killed his father. He’d imagined it so many times. Now that he was actually here, he was struck by how similar it was to what he’d pictured.

He straightened up and looked around, trying to visualize what it had been like that night. There were lights along the path, but none on the beach. It would have been dark. The nearest bungalow was fifty yards away. It was easy to understand why no guests had heard or seen anything unusual that night.

“And those are the boats over there?” Max asked.

“Yes.”

“Were they that far away at the time?”

“Yes, that’s pretty much where they were.”

They walked along the beach toward the boats. The sand was dry and soft. Consuela removed her sandals and went barefoot.

The boats were pulled up above the high-tide line. Some were small sailing dinghies, others were rowboats with their oars stored inside across the slatted seats. Max gripped the edge of one of the rowboats and heaved. It moved a couple of inches and then ground to a halt in the sand.

“So let’s get this straight,” he said. “According to the police and the prosecution in the court case, my mum killed my dad over there, then dragged his body all the way along the beach. That’s…what? About eighty yards? My dad was six feet tall and must have weighed a hundred and eighty pounds. My mum’s five foot five and maybe a hundred and twenty pounds. She then supposedly lifted my dad’s body into a rowboat, single-handedly dragged the boat down to the water, and rowed out to sea to dump his body. I don’t believe a word of it. Could you have dragged a man’s body that far?”

Consuela thought for a minute. “No, I don’t think so.”

“And the boat. You try pulling it.”

Consuela hooked her hands over the edge of the rowboat and pulled back with all her strength. The boat didn’t move even an inch.

“How do guests get the boats into the water?” Max said.

“There’s a hut over there—you see it? There are two attendants on duty during the day. They put the boats in the sea. But they don’t work at night.”

“Have you got the camera?”

Consuela rummaged in her shoulder bag and handed Max the small digital camera they’d brought with them. He snapped a few shots of the area, showing the size of the boats and their position in relation to the rocks. Then he turned to face the sea. The beach shelved quite steeply. Angry white-capped waves were rolling in and breaking on the sand with a thunderous roar. You’d have to be a confident swimmer to go out into the surf. Not that there were many swimmers in the water. At Playa d’Oro, if you wanted to swim, you used one of the hotel pools. The sea was far too wild for most of the guests. It had waves, seaweed, creatures lurking at the bottom—and no waiters to bring out your drinks.

“The police sent divers down, didn’t they?” Max said. “To look for Dad’s body?”

“Just one, I believe,” Consuela answered. “The Santo Domingo police only have one diver. And I don’t think he looked very far.”

Max scanned the coastline. There were a few rocks out in the middle of the bay and, away to the south beyond the headland, the distinctive outline of Shadow Island. But there was an awful lot of open water. If a body had been dumped out there, the chances of finding it were minuscule.

Max took a few more photos. “What do you think really happened?” he said to Consuela.

He’d asked her that question a lot over the past two years, but Consuela never committed herself to a definite answer. “You know I don’t know, Max.”

“But if you had to speculate. Now you’re back here and can see the area again.”

Consuela gave a slight shrug. “It had to have been a man—maybe more than one—who dragged or carried your father’s body that distance. Not many women—and certainly not your mother—could have done it.”

“And their motive?”

“I don’t know.”

“Not robbery, we know that. Why would anyone have wanted to kill Dad?” Max looked out across the sea again. A small fishing boat was chugging back to Rio Verde. It was close enough to the shore for him to see the skipper at the wheel, a second man lounging back in the stern.

“You think Dad’s body is somewhere out there?”

“Don’t think about such things, Max,” Consuela said with a shudder. She watched him discreetly, to see how he was taking all this. She’d been opposed to coming to Santo Domingo, but maybe it was a good thing for Max to be here now. Maybe it would help him come to terms with what had occurred.

“That’s what we’re here for,” Max said. “To think about Dad, to figure out what happened to him.”

He had prepared himself for this moment. For his visit to the last place his father had been seen alive, the place where most people—maybe everybody except Max—believed he had been killed. It was such a beautiful, idyllic spot. The idea that his father had died here was horrific. Was it true? Had he really been killed just a few yards away from where Max was standing now? And was his body really out there in the depths of the ocean?

He had been coping well up till now. He’d focused on the business at hand—examining the area where it had all happened, getting a feel for the location. But now that he’d done that, his mind was starting to dwell on his emotions. He was picturing what might have taken place, seeing his father’s face again, and it upset him. Suddenly, he didn’t want to be there anymore. He wanted to get far away from Playa d’Oro.

“Let’s go,” he said abruptly. “I’ve had enough of this place.”

9

SEEING THE FISHING BOAT OUT ON THE SEA had suddenly reminded Max of something. Alexander Cassidy had chartered a boat during his stay in Santo Domingo and gone out fishing. Max had never known his father to take the slightest interest in fishing. Boats had never appealed to him either. He’d been a bad sailor, seasick even when it was calm, and the waters off Santo Domingo were anything but calm.

What had his mum said at Levington Prison on Sunday? Max’s dad had wanted to get away from Playa d’Oro, so he’d gone into Rio Verde and hired a boat at the harbor. He’d hired the boat’s captain, too. Fernando Gonzales.

In the afternoon, after he and Consuela had returned to their hotel, Max went looking for Fernando Gonzales. Consuela didn’t go with him. Something—maybe the long flight from Britain, maybe the hotel food the night before—had upset her stomach. Like most of the population of Rio Verde, she had retired to her room for a siesta. It was baking hot outside, and the locals knew better than to venture out into the midday sun. But Max didn’t want to stay inside and rest.

Lea

ving his room key at reception, he went out into the city. The streets were quiet. There was very little traffic. All the shops and offices had closed for a few hours, leaving only a handful of restaurants and bars open. He walked down the hill. Max didn’t have a map of Rio Verde, but he knew that if he kept going downhill, sooner or later he’d have to arrive at the harbor.

The city had been built in tiers up the hillside next to the river. Large parts of it—particularly the Old Town, where the Hotel San Rafael was located—predated the invention of the motorcar. The streets running horizontally along the slope were narrow, intended for horse-drawn carts or donkeys, and the streets running vertically weren’t really streets at all—they were steep alleys, many of them simply long flights of twisting steps.

Max went down one set of steps, then another. The high buildings on either side blocked out the sun, but even so it was unpleasantly hot and humid. After a few minutes, Max could feel sweat running down his back, and he wondered whether he might have been better off staying in the hotel with Consuela and having a siesta.

He came to a T junction, where a street cut across his path from right to left. On the far side was an uninterrupted line of houses and shuttered shops. To keep going down the hill he’d have to turn left or right and look for a break in the buildings, maybe another flight of steps. But which way to go?

He turned right and almost immediately realized he’d made a mistake. The street was starting to veer up the hill. He turned and went back the way he’d come. As he reached the steps he’d walked down only seconds earlier, a man burst out in front of him, obviously in a hurry. Max couldn’t stop in time. The two of them collided.

“¡Perdón!” Max said, using one of his few words of Spanish.

“What?” the man exclaimed in English. “Oh, sorry.”

Max stepped back and saw who it was: Derek Pratchett. The salesman was red in the face and sweating heavily. His cheeks and forehead were dripping, and there were damp patches under the arms of his shirt.

“I say, what a surprise. Fancy bumping into you. Literally bumping into you.” Pratchett gave a feeble laugh. “You’re not hurt, are you?”

Attack at Dead Man's Bay

Attack at Dead Man's Bay Paganini's Ghost

Paganini's Ghost Escape from Shadow Island

Escape from Shadow Island The Rainaldi Quartet

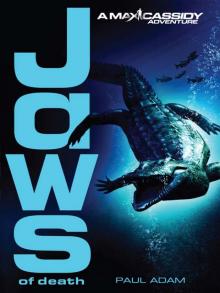

The Rainaldi Quartet Jaws of Death

Jaws of Death